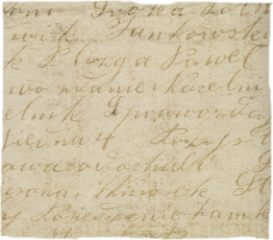

One of the challenges of writing historical fiction is that we can’t know – personally and intimately – what it was like to live then. Diaries, oral history, memoirs, or contemporary scholarly books and novels can give us insights and glimpses into how the transcriber of those words thought and felt, but can they really be taken out of the context of the time and still resonate with inherent nuances? When writing historical fiction this is what we have to try to achieve.

Popular culture interprets a lot of things for us (whether we like it or not). It’s all about the weight we choose to give something and the lens through which we look at and define things. Dame Hilary Mantel in the first of her 2017 BBC Reith Lectures said:

Evidence is always partial. Facts are not truth, though they are part of it – information is not knowledge. And history is not the past – it is the method we have evolved of organising our ignorance of the past.*

Part of how we define the nature of our lives is by what we know they are not. We are not poor because there are people much worse off than us; on the other hand, we are not rich if we compare ourselves to all those with more worldly goods than we possess. It is all relative. And the scales change depending on the era, society, race, gender or age group we are measuring against.

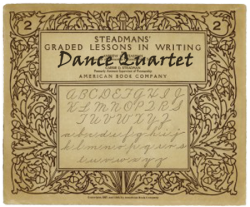

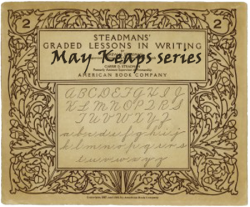

When I tell a story of May Keaps going about her life in 1920, I can’t know how her personal scales of relativity would have differed from her mother’s or her grandmother’s, in the same way as I can’t un-know my experience of being alive today. And you are in the same position when you read my novels and try to imagine yourself as a young woman moulded in her teens by the death and destruction of the Great War. Populating historical fiction is an exercise – from both sides of the page – in trying to strip away the externals to leave us with a naked humanity that would be at home anywhere in any place, at any time.

Historical fiction comes out of our greed for experience. Violent curiosity drives us on, takes us far from our time, far from our shore, and often beyond our compass.*

You can read more pieces inspired by Dame Hilary Mantel’s fabulous Reith Lectures here:

The past in the present

*From: THE DAY IS FOR THE LIVING.